© EuroFootball.com

© EuroFootball.com

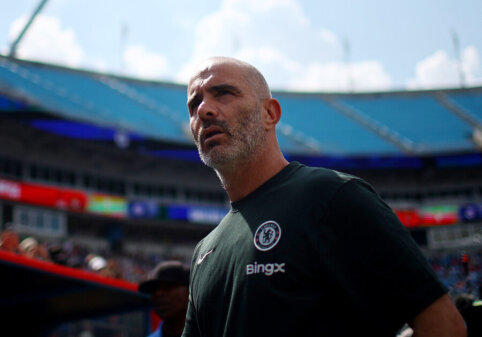

In the section "Tribūna" - an article by Valdas Dambrauskas, a well-known Lithuanian coach working in England, on the problems that have affected the homeland of football when training new players.

Lately, there have been very heated discussions in English football. Why does a country where football is unquestionably the number one sport and the league is one of the strongest in the world not produce players of high mastery? The strongest club coaches - Alex Ferguson, Arsene Wenger, and Jose Mourinho criticize the policy of developing young players.

What happened, what doesn't work in the system of training young footballers? The best football specialists in the country are trying to answer these questions. The English football school is one of the oldest and most famous in the world. In Lithuania, the system of training young footballers is only being created. It would be good if we learned from others and did not repeat the same mistakes...

Let kids play!!!

In recent weeks, the "Sportsmail" investigation regarding the training of young footballers in academies has caused a huge uproar among the country's coaches, managers, and players. In this article, Tomas Stathamas, who has been working as a coach at the Manchester United academy for 13 years and is the director of the Repton football school, shares his thoughts about what is wrong...

"Sir Trevor Brooking believes that we urgently need to make changes if we want our players not to lag behind technically and tactically compared to players from other countries. I agree, but the main question remains - what should we do? The main problem in our country is that children's football is led by adults who aim to impose adult ideas, values, tactics, and pressure on them."

"Most children gain experience in football only in official club training sessions, where enthusiastic and well-meaning coaches present complex exercises, instructions, and explanations. It looks good, sounds wise, impresses parents, but it causes children's astonishment, boredom, frustration, and the question: "When will we play football?" Our youngest players need supervisors and assistants to encourage their progress. Why do I think so? First of all, for many years, I studied what the best players in the world did until the age of 11? Without exception, in their early years, they played football without adult intervention, formal training, or organized championships or matches."

"Technical, exciting, creative players like Matthaus, Puskas, Best, Maradona, and Zidane developed in the streets, parks, and even dump yards near where they lived. They played with other younger and older children, with all kinds of homemade balls. They played alone, one-on-one, three-on-three, ten-on-seven, but... They played hour after hour, day after day."

"Secondly, after watching and interacting with children for many years, I developed some ideas about how children easily and joyfully learn. They imitate, copy, pretend, experiment, take responsibility and risk, make decisions and mistakes, use their imagination, fantasy, and dreams. They do not need to be pushed or forced, they do not need to be told what to do and what not to do. Children need the freedom of play! The main way to develop a happy, active, healthy, and motivated child - as well as technical players - is to provide them with the freedom of play."

"It has produced great players in the past and up to this day develops players in Brazil, Portugal, Nigeria, and Ivory Coast, from where most of the best, most technical players come. Sadly, the freedom of play, where children create and adapt by their age and environment, free from adult influence, is completely dead in modern Britain. The main thing today that concerns all those who love football is: how can we teach children to enjoy football freedom, hour after hour, every week?"

"When some of the best young players in the country up to the age of 10 come to me for training at Manchester United, they bring enthusiasm and love for the game. If it fades means I've lost. So I give them what they want! I prepare them - or let them prepare themselves - games and challenges where they can dribble, twist, run, attack, score, have fun, have lots of ball contacts and most importantly compete."

"So, what do I do? I support them, cheer for them, encourage, congratulate, laugh, and enjoy watching fantastic football played by happy, motivated children. I also set them boundaries of behavior and effort. Within certain limits, they can express themselves in a safe, healthy, positive environment where no one punishes or criticizes them. They repay me by playing daring, brave, attacking football."

"They do incredible things not because they are trained every day and told how to do it, but because they are not told how to do it. No one ever told them they can't do something, no one ever told them what they can't do. Not me, the coach, but the children are at the center of the learning process. Their natural instincts are much stronger than anything I can tell them."

"It took me many years to reach this point, and it is certainly not easy for a competitive person like me, but it is what I would unconditionally recommend to every coach: Leave your ego behind, relax, step aside, and let the kids play!"

How did I learn to play?

Ronaldinho: "I spent a lot of time practicing with "Gremio". After training, I played indoor football. Then I played street football with friends, and when I got home with my brother. Football has always been and will always be my life."

Zinedine Zidane: "Everything I achieved in football is thanks to the time I spent playing football on the street with my friends."

Diego Maradona: "I think we were street kids. If our parents were looking for us, they knew where to find us. We were always there, chasing the ball."

Ronaldo: "Every time I left home, I fooled my mom. I told her I was going to school, but I always went to the street to play football. The ball was always at my feet. In Brazil, every child starts playing football very early in the streets. It's in our blood."

Stanley Matthews: "I always ran to the waste ground near our house, where boys from surrounding houses would gather to kick the ball. Jackets were put together as goalposts, and the game was ready... If the weather was good, we played 20 against 20, if not, then we played 6 against 6. We didn't need referees. We followed the rules of the game. It taught us that we couldn't do whatever we wanted, and if you didn't follow the rules of the game, you spoiled the game for everyone. That's how the game prepared us for life... When I wasn't playing football with friends, I played alone. I had a rubber ball and spent hours kicking it against the house wall."

Ferenc Puskas: "I am very grateful to my father for all the training I didn't have..."

Cristiano Ronaldo: "I learned everything I know by playing on the street."

Lost youth academies...

"Gordon Brown talks about England's chances of hosting the 2018 World Cup, but will the idea be as attractive if England has no chance of winning or even passing the first stage of the tournament? As scared as I am, that's exactly what I think it should and will happen," said former Director of the English Football Association Howard Wilkinson. Ten years ago, he was the man who revolutionized the strategy for developing young footballers. Now he himself believes that this development program has lost its face.

"The decline of young talents in England without the opportunity to shine and could completely disappear in the near future. The main attitude is: what problems? The Premier League is amazing, we have great footballers, fantastic coaches, and the money to attract them here. But I worry about the local young players' development, as they are the crucial factor in the long-term development of our football," said Wilkinson.

He was one of the fiercest advocates for professional clubs' rights to nurture the generation in their academies. He broke the hundred-year tradition of developing footballers in schools and local clubs. But now he fears that many talents from 18 to 21 are being lost. Those who succeed can be counted on one hand - Wayne Rooney, Aaron Lennon, and Micah Richards became first-team players, but many more talented players did not receive such opportunities. Coaches do not want to leave their fate in the hands of young, inexperienced academy talents.

"A president of a Championship club admitted to me that he does not know if it is profitable to invest in the education of young footballers since he cannot give them a chance to play. Promotion to the Premier League is worth £50 million. It becomes a financial matter, and clubs cannot earn if they do not fill their teams with experienced players," Wilkinson said.

Reserve teams are heavily criticized for their disorganization. Main squad players do not get to play for weeks, and academy graduates are loaned to other clubs at the first opportunity. Arsenal's trio of Niklas Bendtner, Sebastian Larsson, and Fabrice Muamba made a good impression at Birmingham club, and Arsene Wenger trusts Steve Bruce (Birmingham coach) to nurture them. However, Jeremie Aliadiere started just 13 games in the starting lineup last season and traveled around Celtic, West Ham, and Wolves clubs.

Now he has returned to Arsenal and plays an important role in the club in cup tournaments, but where is England's youth? 23-year-old former Stoke goalkeeper Peter Fox's son David Fox impressed Manchester United coaches. He played in all the England national teams from 15 to 20 years old, was the captain of Manchester United's reserve team, but quickly realized that a player had to be very special to get a chance to play for the first team. Now he has an 18-month contract with Blackpool.

"I joined United when I was 16 years old, right after high school, and always believed I could play at the highest level, but quickly realized it would be very hard to achieve," the player said. - "The demand for success is so great that foreign and other first-team players are far ahead. We had better players in the Middlesbrough academy, but we couldn't improve because if the club wanted another center-back, they simply bought one. I had to move elsewhere if I wanted to make a career."

25-year-old Tomas Kearney hoped to achieve something as a center-back at Everton, but now, after a short spell at Bradford, he plays for Halifax: "I sacrificed a lot, but as soon as you leave the academy and enter the reserve team, the way is always blocked by older players or foreigners who need playing minutes to stay physically fit. Coaches simply do not give the youth a chance."

Wilkinson has a radical solution. He suggests that smaller clubs nurture and care for players for bigger clubs. If clubs like Notts County, where he is a director, were managed and financially supported by a Premier League club, there would be less pressure regarding the required result. Coaches could develop players, and fans would see a team made up of tomorrow's stars.

"Under the right conditions, I would be satisfied to see Notts County do that," Wilkinson said. - "I wouldn't want to see it as a loss of identity. I would like to see it as a partnership."

"If youth team coaches do not win matches, their abilities are questioned. So, we have youth teams for which, like first-team clubs, the most important thing is not player development but the result," said former FA director and Charlton coach Les Reed.

Currently, more than 40 clubs have the typical academy status for English football, but they are supervised by two different organizations. The Premier League is responsible for the standards of 18 academies, and the football league for the remaining 22. "Self-preservation" protects academies from penalties if they do not have the required pitches or coaching qualifications. This is a constant headache for the Youth Development Director of the Football Association, Sir Trevor Brooking.

Eleven-year-olds in England lag behind the French, Dutch, or Spanish in technical skills, but England's football bosses spend more time arguing about who is responsible for this problem. Although it is universally recognized that youth education is very important, plans for the National Football Centre in Burton upon Trent are frozen, while Ireland, Turkey, and Latvia are building youth education centers based on one of the best examples in the world, which is Clairefontaine in France.

According to Brooking, in most countries, youth education is in the national Football Associations: "Investors need to find a solution because England is rapidly falling behind other countries technically. If we don't take quick action, that difference will become even greater."